The Factor Archives: Shareholder Yield

By Jamie CatherwoodNovember 2019

While they may not have been known by the same names, many modern investment factors have historical roots stretching back centuries. This series, The Factor Archives, provides historical context on the six factor themes underlying OSAM’s investment process. You can also find other posts from the Factor Archives series here.

“Mandatory stock buybacks—like the 6% to 10% dividends that were customary at the time—appear to have been intended to keep management from pocketing or wasting the public’s wealth. Anything that kept profits from piling high in a company’s coffers could help deter managers from stealing, squandering or abusing their power.”

- Jason Zweig, (The Wall Street Journal)1

THE FACTOR THESIS

In our view, management teams serve their shareholders in two capacities: (1) Generate profits and (2) Efficiently allocate those profits for shareholders’ long‐term benefit. In an analysis of corporate allocation over several decades, we find that the most rewarding way to allocate capital is by returning it to shareholders.

Recognizing both the positives and negatives of each method, our approach aims to capture the benefits of both dividends and buybacks. The Shareholder Yield factor is the sum of a stock’s dividend yield and the percentage of net share buybacks over the previous twelve months.

THE EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE

In fact, one of the most effective U.S. stock selection strategies in recent decades has been buying stocks in the midst of repurchasing significant quantities of their own shares.

The chart below summarizes our research on Shareholder Yield. Decile 1 represents the group of stocks rewarding shareholders with high levels of dividends and buybacks; decile 10 shows companies generally not paying dividends and issuing shares. The chart demonstrates that the stocks with high Shareholder Yield outperform the All Stocks Universe by 3.5% annually.

HISTORICAL ORIGINS: SHAREHOLDER YIELD IN THE WORLD’S FIRST MUTUAL FUND

An early example of Shareholder Yield is found in the world’s first mutual fund, Eendragt Maakt Magt (Unity Creates Strength). Founded in 1774 by a Dutch broker named Abraham van Ketwich, the diversified strategy was equally weighted across ten categories of bonds and loans. Similar to modern ETFs, the fund offered small investors cheap access to a portfolio capturing the broader market.

While the fund’s prospectus promised an annual dividend of 4%, it also outlined an innovative buyback program representing the first example of Shareholder Yield.2 Financial historian K. Geert Rouwenhorst, an expert on these early mutual funds, notes:

“Not all investment income from the underlying portfolio would be passed on to the fund investors as dividends; rather, a portion was to be used to retire [repurchase] shares by lot at a premium over the par value of the shares and also to increase dividends to some of the outstanding shares.”3

This is similar to the modern benefits of corporate buybacks, which increase Earnings Per Share (EPS) by reducing the number of outstanding shares via repurchases.

High Conviction Buybacks

OSAM’s approach to Shareholder Yield focuses on identifying ‘High Conviction Buyback’ companies, which repurchase over roughly 5% of their outstanding shares, and at cheap valuations.

In the case of Eendragt Maakt Magt, the managers certainly showed conviction in repurchasing their shares at a steep discount. In 1811, the fund repurchased shares on the open market at a 75% discount, or 125 Guilders a share. When the fund eventually closed, these shares were each worth 561 Guilders. Van Ketwich was clearly a true value investor.4

In fact, van Ketwich’s funds not only contained a Shareholder Yield component, but his second fund, Concordia Res Parvae Crescunt, is credited as the world’s first value fund. The prospectus stated that the strategy favored:

“Solid securities and those that based on decline in their price would merit speculation and could be purchased below their intrinsic values… of which one has every reason to expect an important benefit”5

Even in 1779, Shareholder Yield and Value were a powerful combination. A truth still evident today:

A HISTORY LESSON: THE DUTCH EAST INDIA COMPANY & 18TH CENTURY BUYBACKS

Shareholder Yield is a powerful tool for identifying good management teams, since it represents efficient capital allocation, and returning cash to shareholders. This section dives into early examples of Shareholder Yield’s underlying components: Dividends and Buybacks.

Dividends

The modern stock market began in 1602, when shares of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) traded on the Amsterdam Exchange. However, despite an incredible business monopoly on trade, and incessant demands from shareholders, the VOC did not pay a dividend until 1610. Even still, this first dividend was paid in spices! Shareholders received “mace at a value of 75% of the nominal capital”. It wasn’t until 1612 that the company finally paid a cash dividend.6

The VOC’s early years were marred by constant criticism and complaints from shareholders over management’s poor allocation of capital, and dividend policy.

Beginning in 1609, the infamous first short-seller, Isaac Le Maire, published a pamphlet levying three primary criticisms against management:7

- The company’s rising debt levels reduced shareholders profits to the point that dividends could not be paid.

- The board was not open to receiving advice, or hearing arguments and complaints from investors.

- Directors were “enriching themselves to the detriment of shareholders while trying to get the obligation to publish accounts [financial statements] waived.”

While he lost many other battles with the VOC, the company’s decision to issue dividends (even in spices!) the following year yielded a definitive victory for Le Maire. Despite this temporarily satisfying shareholders, however, the pamphlets and petitions persisted. In 1622, a group of disgruntled shareholders criticized management for wasting capital:

“That route, however, does not lead through the Strait of Magellan, where they wasted the capital of the company… Each of the directors sells something [to the company] in order to maximize his profits.... But why, my dearest Gentlemen, doesn’t the company organize a public auction, why doesn’t it purchase the goods from anybody who is willing to accept the lowest price? This may save one third of the construction costs of the ships.”

– Dissenting Shareholders (1622)8

As a result, the company’s new charter in 1623 ceded increased oversight, regular audits, and a more frequent dividend program that kept investors happy. Since the modern stock market’s inception, there has been a close relationship between effective capital allocation, and dividend policy.9

Buybacks

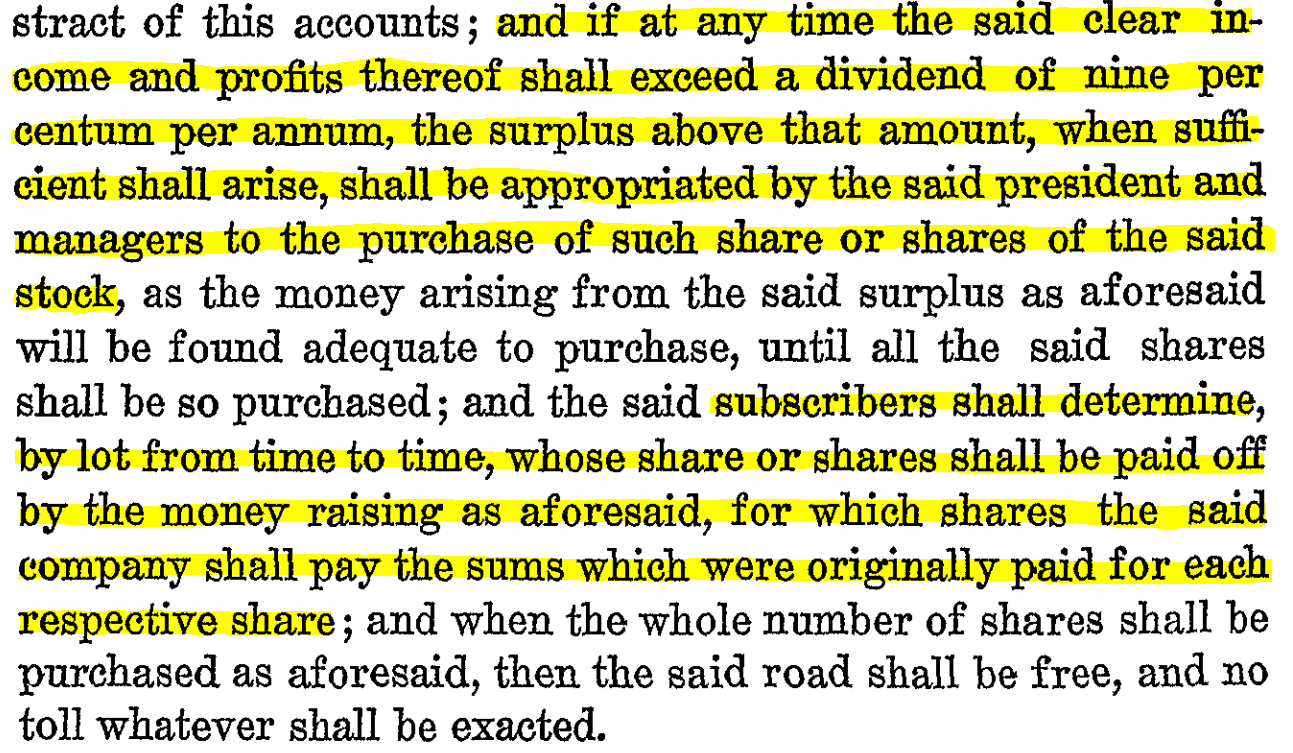

In addition to the Eendragt Maakt Magt example earlier, Jason Zweig’s recent Wall Street Journal article proved that buyback programs have existed in the United States since at least 1798.10 In that year, the Pennsylvania state legislature approved a charter for the Germantown & Reading Turnpike Road Company, provided it committed to repurchasing shares using any excess profits left after paying its 9% dividend.11

Like the early dividends in 17th century Amsterdam, this 18th century buyback program in Pennsylvania aimed to prevent management from wasting shareholders’ capital. Zweig’s article states:

“Mandatory stock buybacks—like the 6% to 10% dividends that were customary at the time—appear to have been intended to keep management from pocketing or wasting the public’s wealth. Anything that kept profits from piling high in a company’s coffers could help deter managers from stealing, squandering or abusing their power.”12

Even our nation’s founding fathers acknowledged management’s tendency to waste capital. Hugh Williamson, who signed the U.S. Constitution, wrote:

“Certainly it is to be desired that Companies were formed and that Copper Mines were diligently wrought, but if Government ever becomes Partners, they will infallibly be the milch cow… I have seen too many of these large companies foolishly and extravagantly managed, where they have proved insolvent. The Paterson manufacturing company- sundry canal companies have vanished into smoke.”13

THE WAY-WAY BACKTEST: ANNUAL DIVIDEND YIELDS OF THE VOC14

MODERN PERSPECTIVES: WHAT NOW?

As the nascent stock market evolved in 17th century Holland, investors recognized the importance of efficient capital allocation, and shareholder distributions. Since buybacks did not yet exist, there were two ways management could do this: cash dividends, and ‘spice dividends’. Roughly two hundred years later, the Pennsylvania Legislature implemented a mandatory buyback program for local turnpike companies.

Today, the importance of Shareholder Yield has only increased. Companies have trillions of dollars sitting in cash and easy access to debt capital, increasing the odds of poor capital allocation by management. A prudent move for some firms could be to distribute cash back to shareholders in the form of dividends and buybacks.

The current outlook for Shareholder Yield as an investment factor is increasingly attractive. The bar to qualify for the highest decile of Shareholder Yield has been getting higher as more companies announce buyback programs, and the stocks in this top decile have gradually become cheaper. As outlined earlier, the combination of Shareholder Yield and Value is powerful, and these stocks are consequently poised to deliver strong performance when value comes back into favor.

By using Shareholder Yield in our investment process, OSAM can identify ‘High Conviction Buyback’ stocks that have historically delivered strong outperformance.

Appendix

1 Jason Zweig, ‘The Fireworks Over Share Buybacks Are Duds’, The Wall Street Journal (July 5, 2019)

8 De Jongh, ‘Shareholder Activism’

9 Ibid.

10 Zweig, ‘Fireworks’, Wall Street Journal

11 Chapter MCMXC, Section XX, P. L, The Statutes at Large of Pennsylvania (1798)