The Road to Custom Indexing: Investment Vehicles

By Jamie CatherwoodFebruary 2021

A New Innovation: Custom Indexing

Innovations do not occur in a vacuum. Instead, they often represent the moment that independent paths of evolution and ideas converge, culminating in something entirely unique. This post focuses on the latest financial innovation, Custom Indexing, and its core foundations: democratization of finance, technology, passive beta, active management, ESG, factor exposure, and customization.

OSAM CEO Patrick O’Shaughnessy defined Custom Indexing best when he wrote:

“Like standard indexes, Custom Indexes also invest and rebalance according to a defined methodology. But with Custom Indexes, the methodology is personalized based on an investor’s circumstances and preferences and can be easily adjusted as an investor’s circumstances change. This flexibility is possible because Custom Indexes are implemented through separate accounts, where investors can directly own a custom mix of individual stocks and bonds rather than indirectly owning positions through a collection of funds and ETFs.

Custom Indexing is a technology, and technology often removes barriers. Co-mingled funds and ETFs sit in between investors and the stocks they own. Funds and ETFs have been good to investors and were wonderful technologies in their own rights. But Custom Indexing software, zero commission trading, and fractional share trading mean that in the future, more investors will own their shares directly rather than through mutual funds and ETFs.

If what we’ve seen with Canvas® is any indication of the future, Custom Indexes will be built using dynamic software, typically starting with broad market exposure (i.e. beta) and then accounting for each investor’s needs in areas like taxes and tax treatment, desired returns, income, risk exposures, ESG, and more.”

Understanding that innovations build upon their predecessors, we will look at the development of innovations within investment vehicles and the road to Custom Indexing.

The Birth of Diversified Investment Funds: Eendragt Maakt Magt (1774)

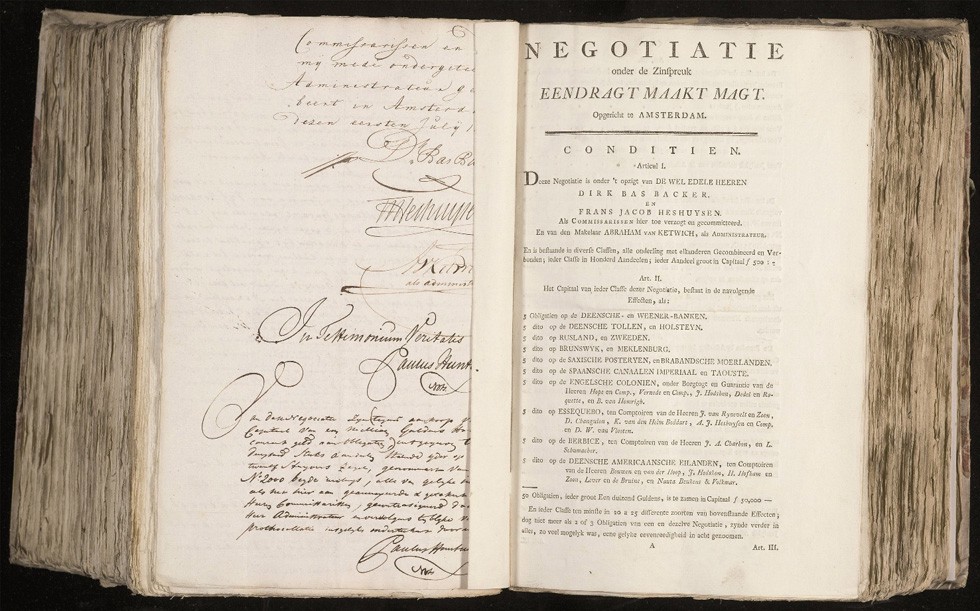

Innovations are often borne out of crisis, and Dutch broker Abraham van Ketwich launching the first ever mutual fund in 1774 is a great example.

“[The fund’s] inception follows the financial crisis of 1772–1773, which bankrupted British banks due to overextension of their position in the British East India Company. When the crisis spread to Amsterdam, several banking houses were pushed to the brink of default. Being a broker, Van Ketwich may have perceived a sentiment for diversified investments among his clientele. Subsequent negotiaties [funds] in which Van Ketwich was involved explicitly advertise the benefits of diversification to attract small investors.”1

As this excerpt shows, the fund’s stated motive was to provide diversified portfolios to investors of moderate means. The fund held some 50 bonds, which were subdivided across 10 categories of bonds (depicted below).

Historian Geert Rouwenhorst writes:

“The prospectus required that the portfolio would be diversified at all times. The 2,000 shares of Eendragt Maak Magt were subdivided into twenty ‘classes,’ and the capital of each class was to be invested in a portfolio of fifty bonds. Each class was to consist of at least twenty to twenty-five different securities, to contain no more than two or three of a particular security, and to ‘observe as much as possible an equal proportionality’.”

The innovation of van Ketwich’s fund was the concept of a pooled investment vehicle. The Dutch broker realized that while smaller investors could not afford to purchase all a portfolio’s underlying securities, he could pool assets into one investment vehicle by selling shares for partial ownership in a broader portfolio. This enabled smaller investors to access a diversified portfolio for a low cost– even by modern standards – at 0.20% per annum.

This was a pivotal moment in financial history and initiated the evolution of investment vehicles and diversification that continue to this day.

Investment Trusts & Active Management Take Hold

Almost a century later in London the first investment trust was launched in 1868 with the founding of Foreign and Colonial Government Investment Trust (FCGT). The motive behind the trust was similar to its Dutch predecessor in 1774, as Section 1 of the trust’s prospectus stated:

"The object of this Trust is to give the investor of moderate means the same advantages as the large capitalist, in diminishing the risk of investing in Foreign and Colonial Government Stocks, by spreading the investment over a number of different stocks…”

An 1875 book covering UK investment trusts summarized what drove the growing interest in investment trusts:

“The causes, which have given rise to the formation of these Trusts, may be briefly described as efforts made to afford to individuals the benefits arising from co -operative action in their investments.”

A writer at the time of the trust’s launch described the management’s view that many retail speculators do not understand the intricacies of investing and lose their savings speculating in single stocks:

“The late Lord Westbury, who, with other persons of standing, founded the first “Foreign and Colonial Government Investment Trust" in 1868. His view was, that, whether a man has a large or small sum to invest, he runs the risk of making a mistake in his individual purchase from not understanding the peculiarities of the Stock; whereas, if he subscribe to an general fund, which (assisted by the advice of persons of experience in such matters) would divide its purchases carefully among selected variety of investments - each member would derive greater benefit with much security from loss by the distribution of the risk over a large average.”

True to its name, the trust focused on foreign government debt both within and outside her majesty’s empire. Founded in a year when Consols (British government bonds) yielded 3.2%, the FCGT was an attractive alternative because of the significantly higher yielding issues in its portfolio:2

The important feature of these trusts that further progressed the evolution of investment vehicles was active management. The key differentiator between these 19th century trusts and the earlier Eendragt Maakt Magt vehicle was an emphasis on actively managing the portfolios.

While today the concept of active management may be pedestrian, the idea that smaller investors could access a diversified and actively managed portfolio was transformative. The popularity of such trusts is reflected in their rapid growth from the first launch in 1868 to 100 trusts by 1890.3

One particularly interesting parallel between the birth of investment trusts and modern innovations like Custom Indexing is that they were both enabled by technology and data. Today we have more data than ever, which increases the analytical capabilities of investors and asset managers. Coupled with an explosion in technology and software, innovative technologies like Custom Indexing are the result. Similarly, over a century ago, the technology and data revolved around the telegraph network connecting investors to informational hubs globally. Cables leading in and out of the NYSE are pictured below:

Professor William Goetzmann has written about the fact that the impact of the telegraph network spawning across Europe and the world was an impetus for financial innovation in Britain.

“Successful development of a financial market requires access to information. If British investors were to place their capital at risk in remote parts of the world, it is only natural to expect that they would have had a strong demand for information about their investments... The speed of information transmission through the telegraph system also improved continuously. In the 1860’s, a telegraphic message could reach London from India in eight and a half hours.

These technological developments changed the informational environment of British investors. By 1870, with the development of the electric telegraph network, British investors could receive news concerning political events world-wide, economic and trade news, and even news regarding the weather and the storms affecting the crops in the colonies.”4

As with most innovations, what was previously “revolutionary” quickly became table-stakes. Investment trusts in the 19th century established a new paradigm in which investors of all means had access to diversified and active portfolios. Building upon this foundation, we will see how new styles and additional offerings related to trusts developed over the ensuing decades in a manner not unlike the rise of ESG products in recent years.

Trusts & ESG

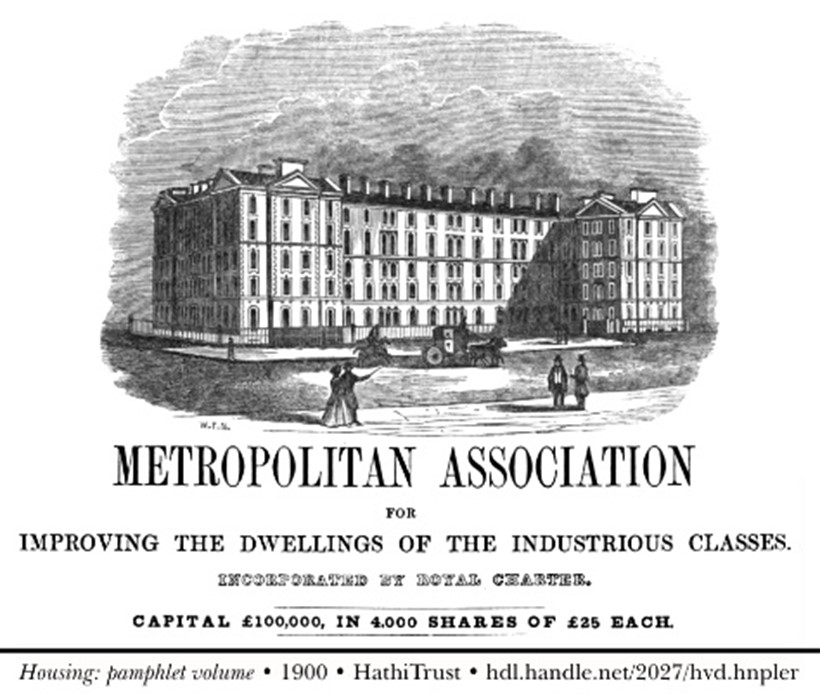

An early form of ESG strategies in the late 19th century demonstrated how additional layers of ingenuity can be built upon the foundation of previous innovations. Colloquially named “Philanthropy & 5%” trusts, the simple yet powerful concept allowed investors to combine their interests in making a positive social impact and generating financial returns by funding philanthropic causes while earning a 5% dividend.

Most trust companies categorized under the Philanthropy & 5% umbrella were focused on one of London’s most pressing challenges: lower-income housing. Victorian England had long struggled to combat the unsanitary and overcrowded housing conditions that were producing slums around London. One historian wrote:

“The task of providing adequate housing for an urban working-class population was a major social issue in the nineteenth century. This 'housing problem' was created by changes in the demand for, and supply of, residential accommodation in inner-city areas. Economic growth and the constraints of transport technology intensified competition for inner urban building sites, and incoming migration swelled demand for working class accommodation. This created a high-rent/low-wage equilibrium in the housing market resulting in the subdivision and multiple occupancy of existing houses and the development of what were known as 'slums'.”5

To address this serious issue, a solution combining philanthropy and investment returns was found in Model Dwelling Company (MDC) trusts.6

“MDCs attempted to develop an institutional form and system of operation which could provide affordable and more salubrious accommodation for the working classes and generate a 'fair' return for those who financed this provision. 'Five per cent philanthropy', as the model dwellings movement has become known…

Investors were encouraged to buy shares in MDCs on which they received dividends. Lord Stanley described this system as a 'fair and equal bargain between man and man' for 'there was no sacrifice of independence on either side. They [the investors] got a fair return for their capital, and the workman got a better quality of lodging.' These companies intended to act for the good of every class through the improved dwellings that were provided, and the secure investment opportunity they offered.”

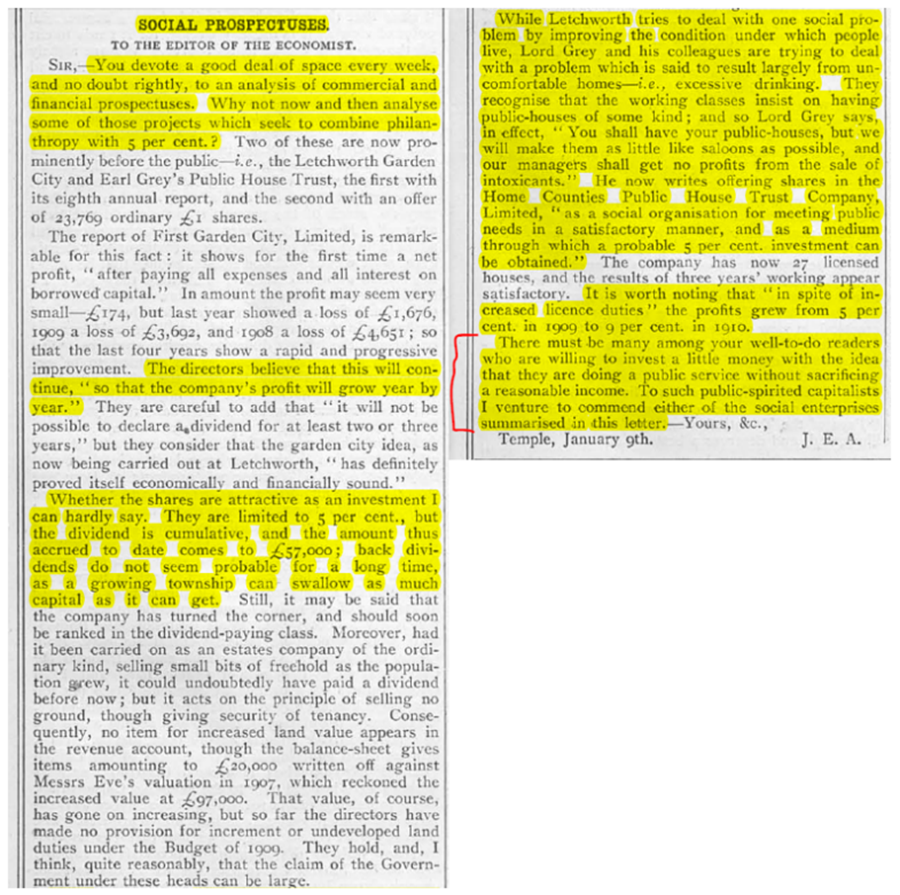

This letter to the editor in an old edition of The Economist offers greater detail on some of these “Social Prospectuses”:

The modern parallels for this excerpt are clear. After the widespread adoption of new investment vehicles that democratized access to financial markets, new ‘themes’ and investment styles were built upon that foundation to satisfy the evolving interests of retail investors. In this case there were early ESG trusts catering to investors that sought out ways to combine the benefits of investment trusts with their desire to make a positive social impact.

The same progression has obviously played out in modern times with the proliferation of ESG ETFs and mutual funds. Everyone can get cheap beta exposure due to the availability of low-cost / passive index funds, which means that more funds are being launched to satisfy more nuanced preferences like ESG.

The problem that investors in Victorian England and today both faced, however, is that these new iterations of underlying investment funds (like ESG) were still handicapped by the fact that they relied upon pooling investor’s money into one investment vehicle. While it is an achievement and positive development that both Victorian and modern investors utilized the investment vehicles of their respective periods to offer unique portfolios aimed at making a societal impact, neither were able to customize the portfolios to the specific desires of each individual investor. This was the tradeoff between democratizing access to markets for smaller investors, which required pooled investment vehicles, and customization

Custom Indexing is an exciting innovation because it does not make that sacrifice, but more on that later.

The First Era of Passive Indexes & Smart Beta: Fixed Trusts

While investment trusts were a key innovation, over time they became increasingly riskier through greater leverage. Their flaws were highlighted in the Panic of 1907 with the fall of the Knickerbocker Trust, and again in 1929 when the extremely levered positions of many trusts led to ruinous outcomes.

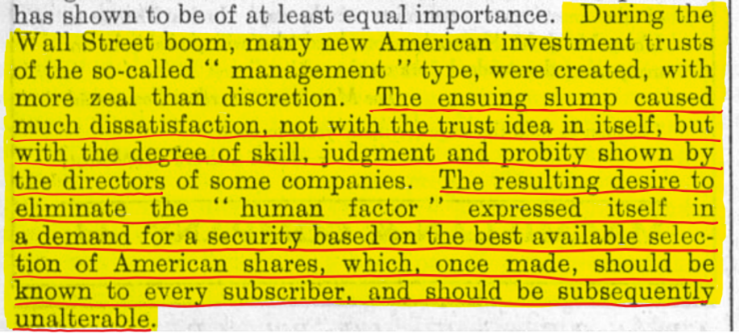

Against this backdrop, the next iteration of trusts – and investment vehicles generally – was formed: Fixed Trusts. Many investors became angry and disillusioned with the actively managed trusts following their poor performance in the 1929 crash. From their perspective, they had paid management fees to these trusts with the expectation that active management would help avoid massive losses in a downturn.

This backlash against actively managed trusts led to the creation of a new vehicle – Fixed Trusts. This early variation of an Index Fund was predicated on the belief that human error and biases were inhibiting good investment outcomes. To correct these issues, Fixed Trust portfolios invested in a set list of securities and ‘fixed’ in that they could not deviate from this initial list. Like previous vehicles, investors could then purchase ‘units’ of this trust for diversified market exposure like SPY ETF shares provide exposure to the S&P 500.

Speaking of the S&P 500, it turns out the company was also a vocal proponent of these passive funds back in the 1930s. This quote below is from “The Standard Statistics Company” (S&P Predecessor) in 1931:

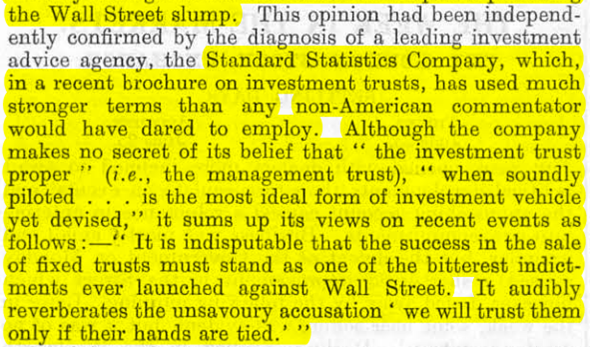

While the introduction of more easily accessible passive investment funds was an important innovation and evolution of investment vehicles, the more interesting component is that it produced some of the first smart beta portfolios and introduced the concept of factor exposures.

This excerpt from The Economist details the triggers that would cause a smart beta-esque Fixed Trust to sell a position based on earnings and valuation metrics.

Breaking Precedent: Custom Indexing

The evolution of investment vehicles leading up to Custom Indexing has been peppered with innovations that were important developments but primarily served one new function or iteration on top of existing vehicles. Custom Indexing is so exciting because it combines all these individual innovations: diversification, factor exposure, passive beta, personal restrictions, tax loss harvesting, and ESG into a single platform.

Studying all these innovations also highlights the ingenuity of Custom Indexing in that it completely bucks the trend of previous investment vehicles. While each of the examples in this post relied upon pooling assets from many investors in order to offer one low-cost diversified portfolio for all, Custom Indexing customizes to the individual rather than the group. This innovation empowers investors to build low-cost, diversified portfolios individually tailored to their specific preferences and goals. Your goals = your strategy.

This was not previously possible, but it is interesting to note that during the Fixed Trust movement of the 1930s, an Economist article stated something akin to Custom Indexing today using window shopping as an analogy:

“When buying a shop window, however, you are bound to buy some articles which you do not favor or which you do not particularly prize.”

With custom indexing, you can purchase only the articles you favor. As technology paved the path for past financial innovations by reducing barriers and friction, technological advancements like free trades, cloud technology, advanced data analysis, and many more make Custom Indexing possible today. The latest innovation further democratizes investing by providing financial advisors and their clients with the ability to invest exactly how they please.

Custom Indexing truly marks a significant evolution in financial history, and we at OSAM are proud to be the industry leader in this new innovation.

Sources

1 K. Geert Rouwenhorst, ‘The Origins of Mutual Funds’ (December 12, 2004). Yale ICF Working Paper No. 04-48

2 Elaine Hutson, The Early Managed Fund Industry: Investment Trusts in 19th Century Britain, University College Dublin (September 2003)

3 Ibid.

4 William N. Goetzmann, British Investment Overseas 1870-1913: A Modern Portfolio Theory Approach, Working Paper (April 2005)

5 Susannah Morris, “Market Solutions for Social Problems: Working-Class Housing in Nineteenth-Century London”, The Economic History Review, Vol. 54, (August, 2001)

6 Ibid

GENERAL LEGAL DISCLOSURES & HYPOTHETICAL AND/OR BACKTESTED RESULTS DISCLAIMER

The material contained herein is intended as a general market commentary. Opinions expressed herein are solely those of O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, LLC and may differ from those of your broker or investment firm.

Please remember that past performance may not be indicative of future results. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product (including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended or undertaken by O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, LLC), or any non-investment related content, made reference to directly or indirectly in this piece will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation, or prove successful. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this piece serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, LLC. Any individual account performance information reflects the reinvestment of dividends (to the extent applicable), and is net of applicable transaction fees, O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, LLC’s investment management fee (if debited directly from the account), and any other related account expenses. Account information has been compiled solely by O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, LLC, has not been independently verified, and does not reflect the impact of taxes on non-qualified accounts. In preparing this report, O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, LLC has relied upon information provided by the account custodian. Please defer to formal tax documents received from the account custodian for cost basis and tax reporting purposes. Please remember to contact O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, LLC, in writing, if there are any changes in your personal/financial situation or investment objectives for the purpose of reviewing/evaluating/revising our previous recommendations and/or services, or if you want to impose, add, or modify any reasonable restrictions to our investment advisory services. Please Note: Unless you advise, in writing, to the contrary, we will assume that there are no restrictions on our services, other than to manage the account in accordance with your designated investment objective. Please Also Note: Please compare this statement with account statements received from the account custodian. The account custodian does not verify the accuracy of the advisory fee calculation. Please advise us if you have not been receiving monthly statements from the account custodian. Historical performance results for investment indices and/or categories have been provided for general comparison purposes only, and generally do not reflect the deduction of transaction and/or custodial charges, the deduction of an investment management fee, nor the impact of taxes, the incurrence of which would have the effect of decreasing historical performance results. It should not be assumed that your account holdings correspond directly to any comparative indices. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to his/her individual situation, he/she is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her choosing. O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, LLC is neither a law firm nor a certified public accounting firm and no portion of the newsletter content should be construed as legal or accounting advice. A copy of the O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, LLC’s current written disclosure statement discussing our advisory services and fees is available upon request

The risk-free rate used in the calculation of Sortino, Sharpe, and Treynor ratios is 5%, consistently applied across time

The universe of All Stocks consists of all securities in the Chicago Research in Security Prices (CRSP) dataset or S&P Compustat Database (or other, as noted) with inflation-adjusted market capitalization greater than $200 million as of most recent year-end. The universe of Large Stocks consists of all securities in the Chicago Research in Security Prices (CRSP) dataset or S&P Compustat Database (or other, as noted) with inflation-adjusted market capitalization greater than the universe average as of most recent year-end. The stocks are equally weighted and generally rebalanced annually

Hypothetical performance results shown on the preceding pages are backtested and do not represent the performance of any account managed by OSAM, but were achieved by means of the retroactive application of each of the previously referenced models, certain aspects of which may have been designed with the benefit of hindsight

The hypothetical backtested performance does not represent the results of actual trading using client assets nor decision-making during the period and does not and is not intended to indicate the past performance or future performance of any account or investment strategy managed by OSAM. If actual accounts had been managed throughout the period, ongoing research might have resulted in changes to the strategy which might have altered returns. The performance of any account or investment strategy managed by OSAM will differ from the hypothetical backtested performance results for each factor shown herein for a number of reasons, including without limitation the following:

- Although OSAM may consider from time to time one or more of the factors noted herein in managing any account, it may not consider all or any of such factors. OSAM may (and will) from time to time consider factors in addition to those noted herein in managing any account.

- OSAM may rebalance an account more frequently or less frequently than annually and at times other than presented herein.

- OSAM may from time to time manage an account by using non-quantitative, subjective investment management methodologies in conjunction with the application of factors.

- The hypothetical backtested performance results assume full investment, whereas an account managed by OSAM may have a positive cash position upon rebalance. Had the hypothetical backtested performance results included a positive cash position, the results would have been different and generally would have been lower.

- The hypothetical backtested performance results for each factor do not reflect any transaction costs of buying and selling securities, investment management fees (including without limitation management fees and performance fees), custody and other costs, or taxes – all of which would be incurred by an investor in any account managed by OSAM. If such costs and fees were reflected, the hypothetical backtested performance results would be lower.

- The hypothetical performance does not reflect the reinvestment of dividends and distributions therefrom, interest, capital gains and withholding taxes.

- Accounts managed by OSAM are subject to additions and redemptions of assets under management, which may positively or negatively affect performance depending generally upon the timing of such events in relation to the market’s direction.

- Simulated returns may be dependent on the market and economic conditions that existed during the period. Future market or economic conditions can adversely affect the returns.